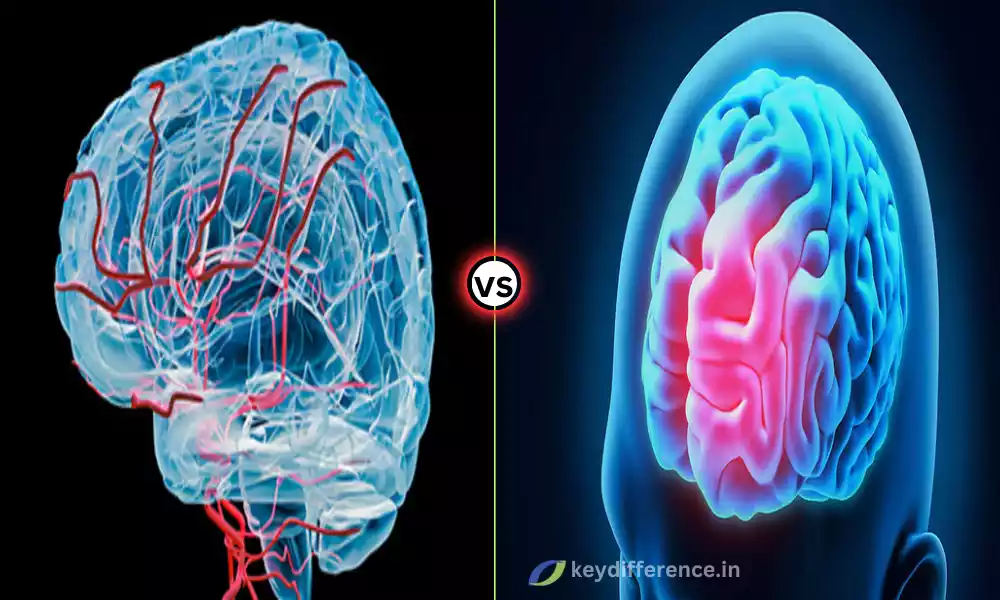

Dementia is an intricate condition affecting cognitive functioning and daily living, including Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) and Vascular Dementia (VaD). Frontotemporal Dementia is especially problematic, while Vascular Dementia is equally alarming.

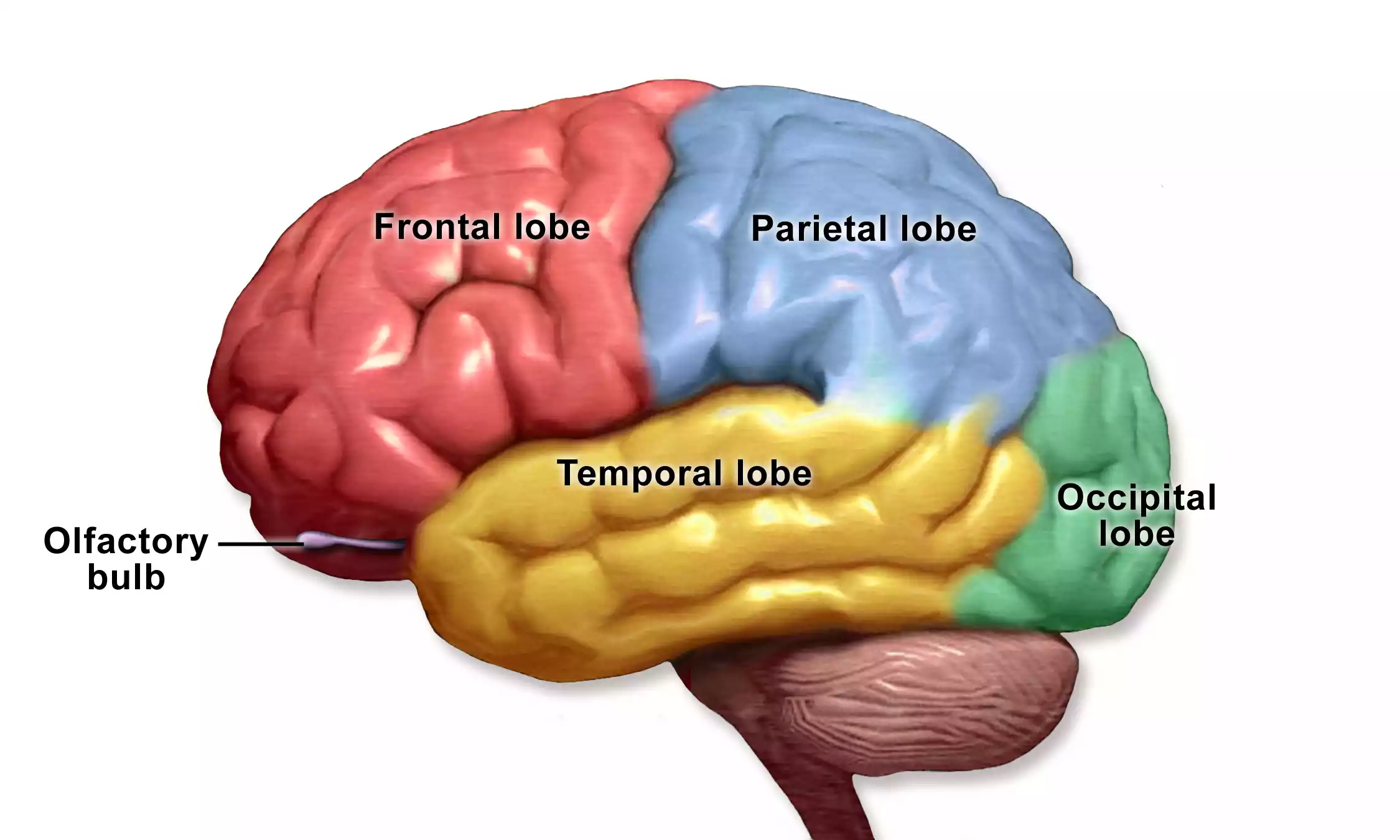

FTD, often manifesting itself in changes in personality and language skills, is typically caused by degeneration in the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. By contrast, VAD is most frequently linked with vascular issues such as stroke causing cognitive function to decline gradually over time.

Understanding the differences between Frontotemporal Dementia and Vascular Dementia is integral for accurate diagnosis, treatment, and patient care. In this article, we’ll look at their distinct characteristics and differences – both from an anatomical standpoint as well as a patient perspective.

Frontotemporal Dementia

Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) is a group of brain disorders that predominantly impact the frontal and temporal lobes, regions associated with personality, behavior, and language.

While other forms of dementia often lead to memory loss as their primary symptom, FTD tends to cause changes in behavior as well as difficulty speaking and communicating in language.

Changes can manifest themselves in many different ways, from increasingly inappropriate actions and loss of empathy/other interpersonal skills, obsessive tendencies, and specific language impairments to increased inappropriate actions or loss.

FTD remains poorly understood, however, its causes are likely linked to abnormal proteins accumulating in the brain and genetic factors – as FTD tends to run in families.

FTD can be difficult to diagnose due to its complex symptoms and requires medical examination including neuroimaging and neuropsychological testing.

While no cure exists for FTD, treatment generally focuses on managing symptoms while support services can make an enormous difference in quality of life for both the person living with FTD as well as their family.

FTD typically begins between 40 and 65, making it one of the youngest forms of dementia and making it an essential area of study and care in neurology.

Definition of Vascular Dementia

Vascular Dementia (VaD) is a form of dementia caused by decreased blood flow to the brain, often due to a stroke or a series of small strokes. This decreased circulation damages areas responsible for memory, thinking, and reasoning functions resulting in impairment.

VaD is characterized by a progressive decline in cognitive abilities, where significant decreases may follow each stroke or ischemic event. Symptoms may include confusion, difficulty with concentration, and reduced ability to organize thoughts as well as physical issues like difficulty walking.

VaD shares many risk factors with heart disease and stroke, such as high blood pressure, cholesterol levels, diabetes, smoking, and high levels of physical inactivity. Therefore, taking measures to improve vascular health may also lower your chances of VaD.

VaD can be diagnosed through reviewing medical history, physical exam, neurological evaluation, and imaging studies such as MRI or CT scans to detect signs of vascular damage in the brain. Unlike some forms of dementia, however, VaD may be at least partially preventable through the management of any underlying vascular conditions.

Treatment for Vascular Artery Disease aims to stop further damage by managing its root causes, such as blood pressure or cholesterol levels, among others.

Medication may also help control these issues while therapy and support can also provide necessary help in order to manage symptoms and enhance quality of life for those living with the condition.

Vascular Dementia highlights the relationship between overall cardiovascular health and cognitive function, and lifestyle choices to maintain brain health. It’s the second-most prevalent cause of dementia after Alzheimer’s, accounting for an overwhelming portion of dementia cases worldwide.

Comparison Table of Frontotemporal Dementia and Vascular Dementia

Certainly, a comparison table can be a very efficient way to quickly understand the differences between Frontotemporal Dementia and Vascular Dementia. Below is a comparison table outlining their key differences:

| Aspect | Frontotemporal Dementia | Vascular Dementia |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A group of disorders affecting the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. | Dementia is caused by problems in the blood vessels that supply the brain. |

| Affected Brain Regions | Frontal and Temporal Lobes | Various, depending on the affected blood vessels |

| Prevalence and Demographics | More common in people under 65 | More common in people over 65 |

| Primary Symptoms | Behavioral changes, language difficulties, motor skills, emotional blunting | Memory loss, confusion, disorientation, problem-solving and planning issues |

| Causes | Genetic factors, neurotransmitter imbalances, Tau protein accumulation | Stroke, blood vessel blockages, cardiovascular diseases |

| Diagnosis Methods | Brain scans, psychological tests, blood tests | Brain scans, medical history, neurological exams |

| Treatment | Medication, behavioral therapy, supportive care | Medication for cardiovascular health, lifestyle changes, cognitive rehabilitation |

| Prognosis | Varies, generally poor due to progressive nature | Depends on cardiovascular health, can be managed but not cured |

| Life Expectancy | Varies, often shorter than other forms of dementia | Varies, can be longer if cardiovascular issues are managed |

This table can serve as a quick reference for anyone wanting to understand the key differences between Frontotemporal Dementia and Vascular Dementia.

Importance of understanding different types of dementia for diagnosis and treatment

Understanding the different forms of dementia is vital for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment. Here’s why:

Customized Diagnosis

Symptom Clarity: Different forms of dementia display their own set of distinctive symptoms. Accurate identification helps clinicians rule out other possibilities that may exist and allows for accurate evaluation and treatment plans.

Early Detection: Recognizing the particular signs associated with different forms of dementia can facilitate earlier diagnosis, which often has long-term positive implications for treatment outcomes.

Specialized Treatment

Targeted Medications: Certain medications work better for certain forms of dementia. Cholinesterase inhibitors tend to be more effective against Alzheimer’s than against other forms.

Behavioral Approaches: Treatments such as behavioral therapy may be best suited to treating Frontotemporal Dementia due to its strong behavioral components, while Vascular Dementia might benefit more from cardiovascular treatments.

Caregiver Prep

Informed Care: Becoming aware of the type of dementia can help caregivers prepare for its unique challenges, including behavioral issues in Frontotemporal Dementia or mobility problems in Vascular Dementia.

Emotional Resilience: Understanding the likely progression of dementia can help caregivers mentally and emotionally prepare for what lies ahead.

Resource Allocation

Focused Support: Support groups or therapies that cater specifically to dementia may prove more successful in providing relief than generalized services.

Customizing dementia care strategies to suit each specific case of dementia is often more cost-effective than taking a blanket approach.

Future Research and Treatment Data Gathering

Accurate diagnosis enables more precise data to be collected that facilitates research efforts.

Clinical Trials: Understanding the differences allows for more targeted trials that can lead to more effective treatments.

By understanding all forms of dementia, healthcare providers can develop more tailored and effective care plans, improving both patients’ quality of life as well as caregivers.

Trouble with problem-solving and planning

Executive dysfunction, commonly referred to as difficulty with problem-solving and planning, is a characteristic symptom of multiple forms of dementia such as Vascular Dementia.

Here’s how this manifests and what steps can be taken to manage it:

Poor Decision-Making: Individuals affected may struggle with making everyday choices such as what clothing or food items to buy.

Problems in Multitasking: Tasks that involve performing multiple steps sequentially may become challenging to manage.

Planning and Organization: Activities that require forethought, like packing for a trip, can become quite time-consuming and taxing.

Problem Solving: Even seemingly straightforward problems can become complex to address, leading to frustration and emotional strain.

Impulsivity: Impulsive behavior may include acting without considering its consequences or making plans in advance.

Neuropsychological Testing: Tests that challenge executive function can reveal areas of weakness.

Brain Imaging: Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRIs) can assist in the identification of damage or abnormalities to areas of the brain responsible for executive functions.

Reducing Task Complexity by Simplification. Step-by-step instructions will be given orally or in writing for every step.

Establish a Routine: Establishing a daily routine can help eliminate the need for planning and reduce anxiety.

Environmental Cues: Use signs, labels, or alarms as reminders or guides for behavior modification.

Professional Help: Occupational therapists offer strategies for managing daily activities and increasing function.

Pharmacological Interventions: While medications cannot completely treat executive dysfunction, they can sometimes help manage associated symptoms such as irritability or anxiety.

Supportive Tools: Incorporating digital apps and devices that aid with planning and reminders.

Understanding the difficulties involved with problem-solving and planning when caring for someone with Vascular Dementia can assist with creating an all-inclusive care plan. Consult healthcare providers for proper diagnosis and tailored management strategies.

Neurotransmitter imbalances

Neurotransmitter imbalances may play a vital role in many neurological and psychiatric conditions, including dementia types like Frontotemporal Dementia. Here’s a closer look at their impact:

Neurotransmitters:

Definition: Chemical messengers that transmit messages between neurons (nerve cells). Synapses connect these neurons, and neurotransmitters carry these signals across them across synapses to reach other nerve cells across synapses.

Types include dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and acetylcholine among many others – with dopamine being the most popular and is known to play an integral part in frontotemporal dementia treatment plans.

Lower Serotonin Levels May Lead to Behavior Changes and Mood Swings Common in Frontotemporal Dementia Dopamine Imbalances Can Contribute to Impulsivity and Disinhibited Behavior.

Glutamate: Excessive levels may lead to neurotoxicity and contribute to cell death and progression of disease.

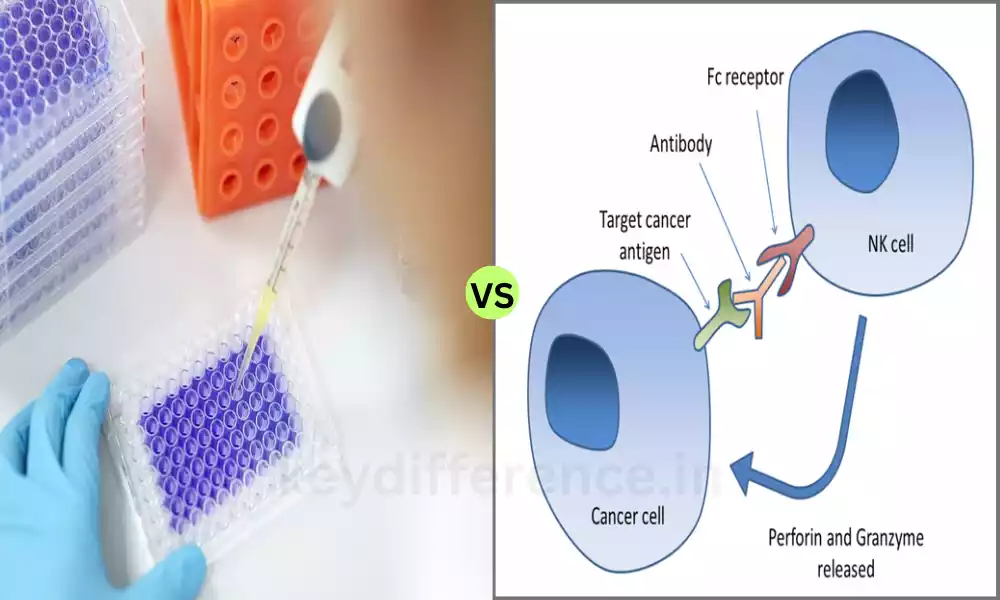

Diagnostic Methods

Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Analysis is one method used for this analysis as it measures neurotransmitter metabolites.

Brain Imaging: PET scans can assist in the identification of altered neurotransmitter activity.

Treatment Approaches

SSRIs: Medication such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can assist with managing serotonin levels to balance mood and behavior while improving both.

Antipsychotics: When treating severe behavioral issues, medications that modulate dopamine activity may be recommended carefully as antipsychotic treatments.

Glutamate Modulators: Drugs designed to control glutamate activity may prove useful, yet must be administered carefully as there may be side effects.

Consequences of Imbalance

Mental Health: Depression, anxiety, and other mood disorders may appear due to imbalance.

Cognitive Decline: Declining decision-making, problem-solving, and focus may occur due to cognitive decline.

Quality of Life: Changes in behavior may strain relationships and make caregiving more challenging, increasing stress for caregivers and straining relationships between care recipients and providers.

Future Research Targeted Therapy: Understanding neurotransmitter imbalances is crucial to creating more effective, targeted therapies.

Biomarkers: Work is ongoing to determine whether neurotransmitter levels can serve as early biomarkers of Frontotemporal Dementia or other dementias.

Understanding neurotransmitter imbalances can provide invaluable insight into the complex pathophysiology of Frontotemporal Dementia and lead to more tailored, targeted treatment plans.

Reference Books

Certainly, if you’re looking for more in-depth information on Frontotemporal Dementia, Vascular Dementia, or dementia in general, the following reference books are highly recommended. These resources can be beneficial for healthcare professionals, caregivers, or anyone interested in understanding these complex conditions better:

Frontotemporal Dementia:

- “The Frontotemporal Dementia Handbook” by Helen Whitworth

- A comprehensive guide for caregivers, offering practical advice and strategies for managing FTD symptoms.

- “Behavioral Neurology of Dementia” edited by Bruce L. Miller and Bradley F. Boeve

- A scholarly resource for healthcare professionals focusing on behavioral aspects of various forms of dementia, including FTD.

Vascular Dementia:

- “Vascular Cognitive Impairment in Clinical Practice” by Lars-Olof Wahlund, Timo Erkinjuntti, Serge Gauthier

- Addresses diagnostic criteria, imaging techniques, and treatment options for Vascular Dementia.

- “Post-Stroke Dementia and Vascular Cognitive Impairment” by Danny Chan, Lars-Olof Wahlund

- Provides an understanding of cognitive impairment post-stroke, including Vascular Dementia.

Conclusion

Understanding the differences between Frontotemporal Dementia and Vascular Dementia is vital for accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and holistic caregiving.

These types of dementia present unique challenges, from their various symptoms and causes to the wide-ranging impacts on executive functions. Real-life examples demonstrate this diversity and complexity for patients and their loved ones alike.

As this field develops, more comprehensive reference books and scholarly resources offer in-depth knowledge, equipping healthcare professionals and caregivers alike with essential tools for improving patient outcomes.